El principio de Pareto es también conocido como la regla del 80-20 y recibe este nombre en honor a Vilfredo Pareto, quien lo enunció por primera vez.

Descripción

Pareto enunció el principio basándose en el denominado conocimiento empírico. Observó que la gente en su sociedad se dividía naturalmente entre los «pocos de mucho» y los «muchos de poco»; se establecían así dos grupos de proporciones 80-20 tales que el grupo minoritario, formado por un 20% de población, ostentaba el 80% de algo y el grupo mayoritario, formado por un 80% de población, el 20% de ese mismo algo.

Estas cifras son arbitrarias; no son exactas y pueden variar. Su aplicación reside en la descripción de un fenómeno y, como tal, es aproximada y adaptable a cada caso particular.

El principio de Pareto se ha aplicado con éxito a los ámbitos de la política y la Economía. Se describió cómo una población en la que aproximadamente el 20% ostentaba el 80% del poder político y la abundancia económica, mientras que el otro 80% de población, lo que Pareto denominó «las masas», se repartía el 20% restante de la riqueza y tenía poca influencia política. Así sucede, en líneas generales, con el reparto de los bienes naturales y la riqueza mundial.

Understanding the Pareto Principle (The 80/20 Rule)

Originally, the Pareto Principle referred to the observation that 80% of Italy’s wealth belonged to only 20% of the population.

More generally, the Pareto Principle is the observation (not law) that most things in life are not distributed evenly. It can mean all of the following things:

20% of the workers could create 10% of the result. Or 50%. Or 80%. Or 99%, or even 100%. Think about it — in a group of 100 workers, 20 could do all the work while the other 80 goof off. In that case, 20% of the workers did 100% of the work. Remember that the 80/20 rule is a rough guide about typical distributions.

Also recognize that the numbers don’t have to be “20%” and “80%” exactly. The key point is that most things in life (effort, reward, output) are not distributed evenly – some contribute more than others.

In a perfect world, every employee would contribute the same amount, every bug would be equally important, every feature would be equally loved by users. Planning would be so easy.

But that isn’t always the case:

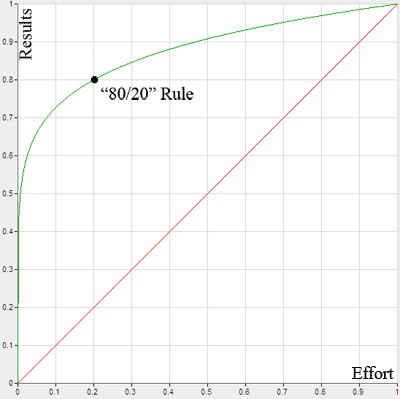

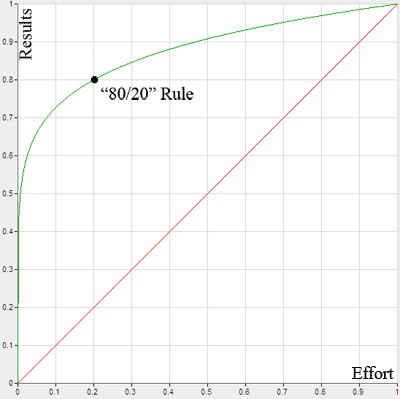

The 80/20 rule observes that most things have an unequal distribution. Out of 5 things, perhaps 1 will be “cool”. That cool thing/idea/person will result in majority of the impact of the group (the green line). We’d like life to be like the red line, where every piece contributes equally, but that doesn’t always happen.

Of course, this ratio can change. It could be 80/20, 90/10, or 90/20 (remember, the numbers don’t have to add to 100!).

The key point is that most things are not 1/1, where each unit of “input” (effort, time, labor) contributes exactly the same amount of output.

20% of workers contribute 80% of results: Focus on rewarding these employees.

20% of bugs contribute 80% of crashes: Focus on fixing these bugs first.

20% of customers contribute 80% of revenue: Focus on satisfying these customers.

The examples go on. The point is to realize that you can often focus your effort on the 20% that makes a difference, instead of the 80% that doesn’t add much.

In economics terms, there is diminishing marginal benefit. This is related to the law of diminishing returns: each additional hour of effort, each extra worker is adding less “oomph” to the final result. By the end, you are spending lots of time on the minor details.

Now let’s deconstruct this video. It’s about 5 minutes long, so each minute is about 20% of the way to completion (of course the video is sped up, but we are only interested in relative times anyway). Take a look at how the car evolved over time:

1:06 (Level 1) – Wireframe

2:00 (Level 2) – Basic coloring

3:05 (Level 3) – Beginning details: rims, windshield

4:04 (Level 4) – Advanced details: shading, reflections

5:05 (Level 5) – Finishing touches: headlights, background

Now, let’s say the artist was creating potential designs for a client. Given 5 minutes of time, he could present:

The point isn’t that #5 is better than #1 — it clearly is. The question is whether #5 is better than five #1s, or some other combination.

Let’s say your customer doesn’t know whether they want a car, a truck, or a boat, let alone the color. Spending the time to create a Level 5 drawing wouldn’t make sense — show some concepts, get a general direction, and then work out the details.

The point is to put in the amount of effort needed to get the most bang for your buck — it’s usually in the first 20% (or 10%, or 30% — the exact amount can vary). In the planning stage, it may be better to get 5 fast prototypes rather than 1 polished product.

In this example, after 1 minute (20% of the time) we have a great understanding of what the final outcome will be. Most of the “work” is done up front, in the sense of deciding the type of vehicle, body style, and perspective. The rest is “filling in details” like colors and shading.

This isn’t to say the details are easy — they’re not — but each detail does not add as much to the picture as the broad strokes in the beginning. The difference between #4 and #5 is not as great as #1 and #2, or better yet, a blank drawing and #1 (the time from 0:00 to 1:06). You really have to look to see the differences on the car between #4 and #5, while the contribution #1 makes is quite obvious.

Lastly, don’t think the Pareto Principle means only do 80% of the work needed. It may be true that 80% of a bridge is built in the first 20% of the time, but you still need the rest of the bridge in order for it to work. It may be true that 80% of the Mona Lisa was painted in the first 20% of the time, but it wouldn’t be the masterpiece it is without all the details. The Pareto Principle is an observation, not a law of nature.

When you are seeking top quality, you need all 100%. When you are trying to optimize your bang for the buck, focusing on the critical 20% is a time-saver. See what activities generate the most results and give them your appropriate attention.

Pareto enunció el principio basándose en el denominado conocimiento empírico. Observó que la gente en su sociedad se dividía naturalmente entre los «pocos de mucho» y los «muchos de poco»; se establecían así dos grupos de proporciones 80-20 tales que el grupo minoritario, formado por un 20% de población, ostentaba el 80% de algo y el grupo mayoritario, formado por un 80% de población, el 20% de ese mismo algo.

Estas cifras son arbitrarias; no son exactas y pueden variar. Su aplicación reside en la descripción de un fenómeno y, como tal, es aproximada y adaptable a cada caso particular.

El principio de Pareto se ha aplicado con éxito a los ámbitos de la política y la Economía. Se describió cómo una población en la que aproximadamente el 20% ostentaba el 80% del poder político y la abundancia económica, mientras que el otro 80% de población, lo que Pareto denominó «las masas», se repartía el 20% restante de la riqueza y tenía poca influencia política. Así sucede, en líneas generales, con el reparto de los bienes naturales y la riqueza mundial.

Understanding the Pareto Principle (The 80/20 Rule)

Originally, the Pareto Principle referred to the observation that 80% of Italy’s wealth belonged to only 20% of the population.

More generally, the Pareto Principle is the observation (not law) that most things in life are not distributed evenly. It can mean all of the following things:

- 20% of the input creates 80% of the result

- 20% of the workers produce 80% of the result

- 20% of the customers create 80% of the revenue

- 20% of the bugs cause 80% of the crashes

- 20% of the features cause 80% of the usage

- And on and on…

20% of the workers could create 10% of the result. Or 50%. Or 80%. Or 99%, or even 100%. Think about it — in a group of 100 workers, 20 could do all the work while the other 80 goof off. In that case, 20% of the workers did 100% of the work. Remember that the 80/20 rule is a rough guide about typical distributions.

Also recognize that the numbers don’t have to be “20%” and “80%” exactly. The key point is that most things in life (effort, reward, output) are not distributed evenly – some contribute more than others.

Life Isn’t Fair

What does it mean when we say “things aren’t distributed evenly”? The key point is that each unit of work (or time) doesn’t contribute the same amount.In a perfect world, every employee would contribute the same amount, every bug would be equally important, every feature would be equally loved by users. Planning would be so easy.

But that isn’t always the case:

The 80/20 rule observes that most things have an unequal distribution. Out of 5 things, perhaps 1 will be “cool”. That cool thing/idea/person will result in majority of the impact of the group (the green line). We’d like life to be like the red line, where every piece contributes equally, but that doesn’t always happen.

Of course, this ratio can change. It could be 80/20, 90/10, or 90/20 (remember, the numbers don’t have to add to 100!).

The key point is that most things are not 1/1, where each unit of “input” (effort, time, labor) contributes exactly the same amount of output.

So Why Is This Useful?

The Pareto Principle helps you realize that the majority of results come from a minority of inputs. Knowing this, if…20% of workers contribute 80% of results: Focus on rewarding these employees.

20% of bugs contribute 80% of crashes: Focus on fixing these bugs first.

20% of customers contribute 80% of revenue: Focus on satisfying these customers.

The examples go on. The point is to realize that you can often focus your effort on the 20% that makes a difference, instead of the 80% that doesn’t add much.

In economics terms, there is diminishing marginal benefit. This is related to the law of diminishing returns: each additional hour of effort, each extra worker is adding less “oomph” to the final result. By the end, you are spending lots of time on the minor details.

A Fun, Non-Math Example, Please

Everything is nice and rosy in the abstract. I want to give you a real example. Take a look at this awesome video of an artist drawing a car in Microsoft Paint. It’s pretty phenomenal what can be accomplished with such a basic tool:Now let’s deconstruct this video. It’s about 5 minutes long, so each minute is about 20% of the way to completion (of course the video is sped up, but we are only interested in relative times anyway). Take a look at how the car evolved over time:

1:06 (Level 1) – Wireframe

2:00 (Level 2) – Basic coloring

3:05 (Level 3) – Beginning details: rims, windshield

4:04 (Level 4) – Advanced details: shading, reflections

5:05 (Level 5) – Finishing touches: headlights, background

Now, let’s say the artist was creating potential designs for a client. Given 5 minutes of time, he could present:

- A single car at top quality (Level 5)

- A reasonably detailed car (Level 3) and a colorized wireframe (Level 2)

- 5 cars at a wireframe level (5 Level 1s)

The point isn’t that #5 is better than #1 — it clearly is. The question is whether #5 is better than five #1s, or some other combination.

Let’s say your customer doesn’t know whether they want a car, a truck, or a boat, let alone the color. Spending the time to create a Level 5 drawing wouldn’t make sense — show some concepts, get a general direction, and then work out the details.

The point is to put in the amount of effort needed to get the most bang for your buck — it’s usually in the first 20% (or 10%, or 30% — the exact amount can vary). In the planning stage, it may be better to get 5 fast prototypes rather than 1 polished product.

In this example, after 1 minute (20% of the time) we have a great understanding of what the final outcome will be. Most of the “work” is done up front, in the sense of deciding the type of vehicle, body style, and perspective. The rest is “filling in details” like colors and shading.

This isn’t to say the details are easy — they’re not — but each detail does not add as much to the picture as the broad strokes in the beginning. The difference between #4 and #5 is not as great as #1 and #2, or better yet, a blank drawing and #1 (the time from 0:00 to 1:06). You really have to look to see the differences on the car between #4 and #5, while the contribution #1 makes is quite obvious.

Concluding Thoughts

This may not be the best strategy in every case. The point of the Pareto principle is to recognize that most things in life are not distributed evenly. Make decisions on allocating time, resources and effort based on this:- Instead of 1 hour on a rough draft for an article you may write, spend 10 minutes on 6 outlines for a paper / blog article and pick the best topic.

- Instead of investing 3 hours on a website, spend 30 minutes and create 6 different template layouts.

- Rather than spending 3 hours to read 3 articles in detail (which may not be relevant to you), spend 5 minutes glancing through 12 articles (1 hour) and then spend an hour each on the two best ones (2 hours).

Lastly, don’t think the Pareto Principle means only do 80% of the work needed. It may be true that 80% of a bridge is built in the first 20% of the time, but you still need the rest of the bridge in order for it to work. It may be true that 80% of the Mona Lisa was painted in the first 20% of the time, but it wouldn’t be the masterpiece it is without all the details. The Pareto Principle is an observation, not a law of nature.

When you are seeking top quality, you need all 100%. When you are trying to optimize your bang for the buck, focusing on the critical 20% is a time-saver. See what activities generate the most results and give them your appropriate attention.

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario